Finding Safety: A Full Guide for Transitioned Women Affected by Sexual or Domestic Violence in the UK (2026)

23 min read

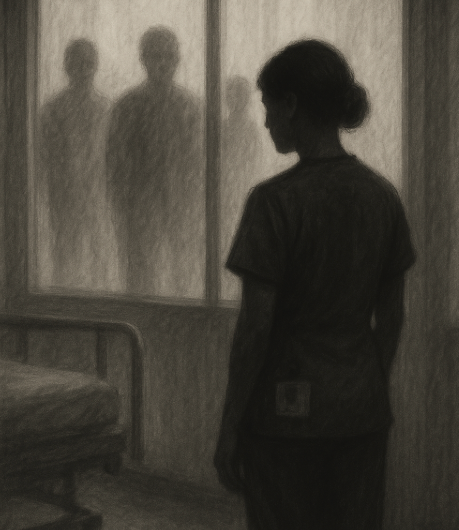

A practical, trauma-informed guide for transitioned women in the UK navigating sexual or domestic violence. This article explains where support exists, and how to protect your dignity and safety...